For my very first post in this blog, I wanted to unite two things that I’m crazy about: jewelry, and art/artists of the 20th century. Surprisingly, very few people know that a lot of those artists (talking about giants as Dali, Picasso, Ernst, Cocteau etc., just to name a few) have designed some jewelry –or even collections. Today I am going to focus on two of them and show you this less known side of their work.

Picasso

Early in his career, Picasso made a series of one-of-a-kind jewelry pieces which he cast in the south of France. He cast about 10 pieces, some in silver, some in gold, with the help of his dentist (you would be surprised to hear how jewelry and dentistry are related!) One of them is the portrait of his son Claude, and another one is of his daughter Paloma. He gave these pieces to Françoise Gilot (their mother). What makes these pieces more extraordinary is that the artist did not sign them, unlike some other collections that he created later in his life. Which means that they were not intended to be sold, but were very personal objects for the artist and his family. On the other hand, satyrs, minotaurs and bulls figured undeniably in many of Picasso’s paintings, and became very important motives for the artist. The Satyr or Faun is a half man, half goat, libidinous— like Picasso himself—creature which the artist represents often as a substitute for himself. Many of his jewelry pieces as well feature one of those creatures.

Picasso’s jewelry shows the artist’s softer side, and they are very special because they are personal. He mostly created jewelry for his lovers. After the death of one of his former loves and muses, Dora Maar, a big number of jewelry pieces made for her by Picasso were found in her apartment, among other paintings, objects and pictures: brooches, rings, sea pebbles turned into jewelry, pre-made jewelry in which he inserted portraits of her…

It is clear now that the most intimate expression of Picasso’s affection was in the jewelry he created for his loved ones: personal, private and unique.

However, he also designed some collections to be sold, which were executed in high-carats gold by a French maker. Those pieces are signed with the artist and the maker’s script signature.

Bull pendant – 23 carats gold

Dalí

Dalí ‘s jewelry is a real expansion of his surrealist art.

Unlike famous artists like Picasso who were not known for the jewelry they designed or made, Salvador Dalí was recognized as a master in this field too. Since 1941, he began to draw jewelry with an abundance of details and a great precision of forms. These were then executed in New York under the control of the artist, in the workshop of his Argentinian goldsmith, Carlos Alemany. Dalí also uses his favorite subjects in his jewelry, like the famous clock positioned on a branch in his Persistence of Memory, painted in 1931.

The Persistence of Memory, 1931

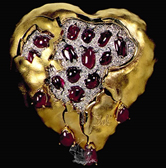

Dalí goes even further in the making of jewelry. He chooses the materials himself: mostly the most precious ones as gold, emeralds, rubies, diamonds, pearls; everything that would help him express his surrealist creative genius in the best possible way. Legend says that his wife Gala, in one of her extravagant demands, asked for “a beating heart made of ruby”. Gala was said to want brilliance and luxury, and Dali started to imagine some extraordinary jewelry to please his wife. For the story, he managed to create a heart made of the most precious materials and even used a mechanism to make the heart beat!

Royal Heart: 18k yellow gold; natural rubies, sapphires, emeralds, aquamarines, diamonds, pearls, garnets

At the end, his jewelry gave a new dimension to Dalì’s existing fame. He even collaborated with fashion designers like Elsa Schiaparelli.

Today, most of Dalí’s jewels can be seen at the Dalí Museum in Figueres, Spain. I would like to conclude with some words that the artist used to sum up his designs: “To history, they will prove that objects of pure beauty, without utility but executed marvelously, were appreciated in a time when the primary emphasis appeared to be upon the utilitarian and the material.”

© 2021 Paola Sleiman. All rights reserved.